Rob Urban Fellowship for Reporting in Central and Eastern Europe

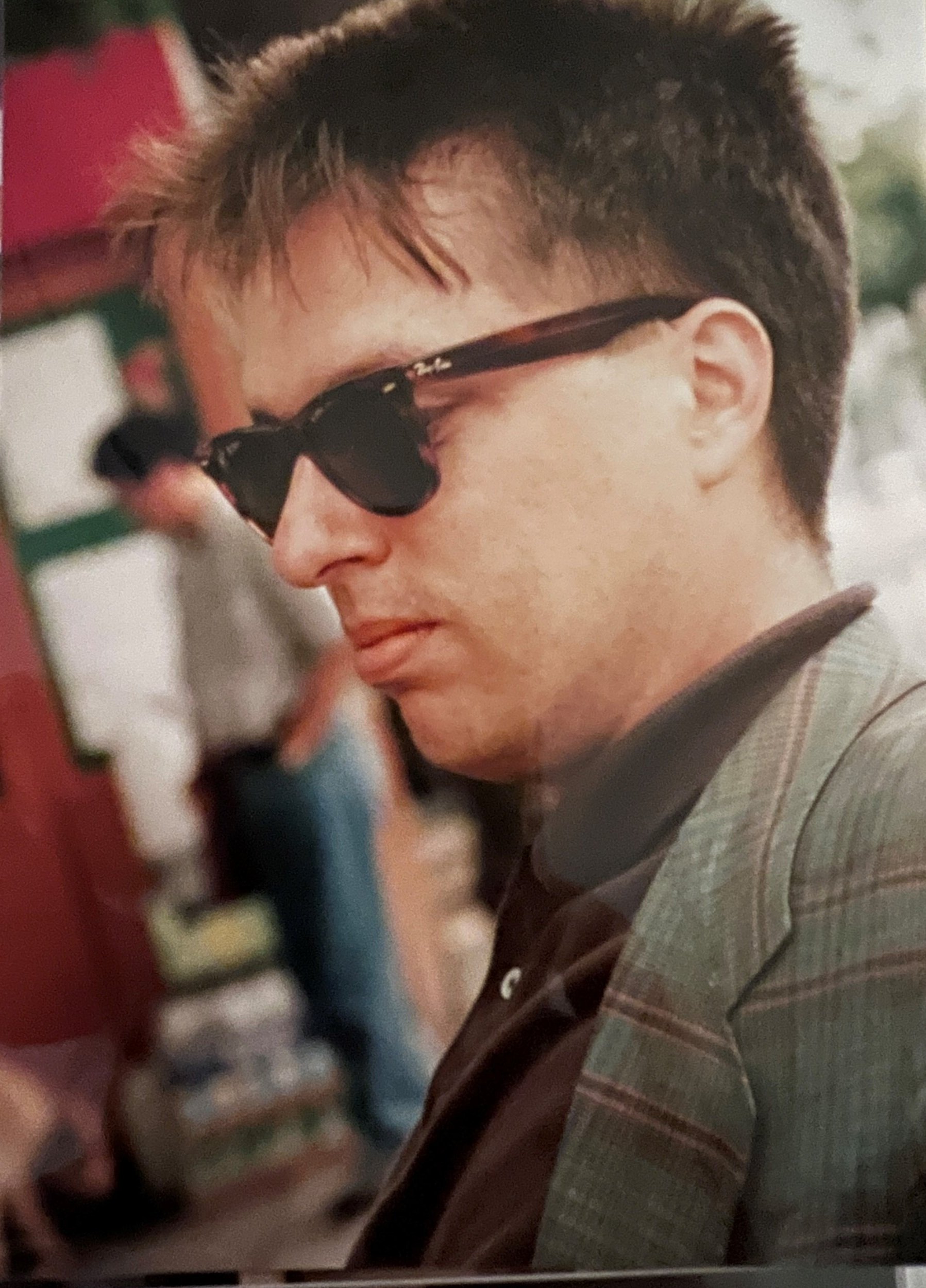

The Rob Urban Fellowship for Reporting in Central and Eastern Europe honors an intrepid financial journalist who helped establish Bloomberg News’ initial presence in the region in the early 1990s, hire the original staff and cover everything from the fraudulent investment schemes that proliferated after the end of communism to the global financial crisis that resulted from Russia’s debt default. Rob, who died suddenly on Sept. 20, 2023 at age 66, developed his investigative chops as a cop and courts reporter at The Charlotte Observer in North Carolina before moving to Prague in 1992. No challenge was ever too daunting and he found himself in many tricky places - reporting in a remote part of Kazakhstan to witness a post-Soviet rocket launch, descending the dark, frigid shaft of a Siberian nickel mine and navigating a dangerous Serbian minefield after the Yugoslav war - in addition to writing daily equities, commodities, politics, banking and economic stories to chronicle the emergence of capital markets and democracies across the region. Rob started a family while living in Eastern Europe - he became a father with the birth of our son Sasha in Moscow in 1999 and our daughter Katya two years later upon our return to the United States in 2001. Rob was a writer at heart and later in life produced many essays about his time overseas. This one, entitled Stalin’s Boots, captures his flair with language as well as his fearless approach to reporting, during a time in his life when his work was both profound and impactful.

—Laura Zelenko

“If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face— forever.”

-George Orwell, 1984

Stalin’s Boots

By Rob Urban

In 1956, 100,000 Hungarian protestors attacked the massive statue of Josef Stalin in Budapest’s City Park with picks and blow torches, destroying all but the larger-than-life black boots of the communist dictator.

The statue was gone, but the sense of menace remains. The giant footwear still evoke an image of the USSR’s Man of Steel stomping out opposition across the former Soviet bloc.

Cults of personality don’t die easily. Often they don’t seem to die at all, even when all that remains after the blow torches and dynamite is a pair of giant brass boots.

Remarkably, the boots survived Stalin’s death, the destruction of Stalin’s statue and even the fall of Communism, which didn’t come until 13 years after his City Park statue was dismantled.

The boots now stand atop their massive plinth at the entrance to Budapest’s Memento Park, a kind of Communist sculpture garden just outside of the city that’s filled with all the other fallen symbols of Soviet domination.

I had come to Eastern Europe in search of giants, just not this kind. I was drawn by Vaclav Havel, the playwright/poet turned president of Czechoslovakia, and Lech Walese, the labor union leader who transformed Poland.

And I found them. Sadly, though understandably, they were also a minority of post-Communist leaders. They were surrounded by plenty of little people, just like in any government anywhere, I guess. There was Vaclav Klaus, the Czech prime minister, Vladimir Meciar, Slovakia’s prime minister. Those guys were so small that they conspired to split Czechoslovakia, to bring it down to their size.

Stalin monuments were erected across the former Soviet bloc, with an emphasis on size and weight. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Khrushchev, his successor, attempted to loosen the grip of his cult of personality. The monuments were torn down across the East Bloc. Most demolitions were sanctioned by Moscow. The boot-clad giant in Budapest was a freelance affair, in the heat of the 1956 Hungarian revolution that was brutally put down by Soviet troops.

Romania had at least three massive Stalin statues, in Bucharest, Brasov and Targu Mures. All three were torn down between 1959 and 1965.

The big Kahuna of all Stalin monuments was in Prague, where the communists were ``more Catholic than the Pope.” The monument was seven tons and stood in Letna Park, overlooking the Vltava River, until 1962, when it was hastily dynamited in the middle of the night in preparation for a visit from Krushchev. The Soviets had come to prepare for Krushchev’s arrival, and were very unhappy to see Uncle Joe’s statue overlooking the whole city. So the Czechs blew it up.

It was later replaced by a giant metronome, and for a few months in 1996 a 36-foot-tall statue of Michael Jackson when he performed in Prague.

Stalin monuments once stood in town squares across Russia, and a few survive even today in some remote villages.

He lives on too in the hearts of many Russians. They carry framed photos of him in parades marking May Day or the Great October Revolution (which took place in November 1917), and they vote for the Communist Party when there’s an election. Kiosks on the streets of Moscow and every big city carry Stalin vodka and Stalin cigarettes. I found it particularly unnerving to see Stalin cigarettes for sale in Norilsk, a former gulag town above the Arctic Circle that is literally built on the bones of hundreds of thousands of Stalin’s victims.

In Budapest’s Liberty Square, on the Pest side of the Danube, stands another statue, a life-size bronze of Ronald Reagan, another politician who favored boots, though of the cowboy variety. His statue seems to be walking purposefully across the square after exiting Hungary’s parliament building. He is in this case wearing ordinary dress shoes.

Still, he was long known for his cowboy boots, his cowboy roles in the movies, and his distinctive cowboy styles of speech and action in office (which could often be alarming in this nuclear age).

“I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever,’’ Reagan ``joked” in 1984, unaware he was speaking into a live mic. “We begin bombing in five minutes.”

To this day, on the website of Reagan’s official presidential library, you can buy a pair of boots designed for Reagan by Tony Lama and bearing the presidential seal. There’s also a watch picturing the late president on its face in a cowboy hat. And for the true Ronald Reagan cowboy experience, they’ll sell you a lovely hand-tooled leather gunbelt.

A pair of cowboy boots that once encased Ronnie’s feet sold at auction in 2016 for $20,000. Cults of personality don’t die easily.

I once had my own pair of cowboy boots, chestnut brown with pointed toes and an indented heel that was more of a maple color. I admit, I loved those boots.

I wore them on a reporting trip to Romania in the mid-1990s. Actually, I wore them pretty much everywhere in those days, but when I remember this particular trip, I think about the boots, mine and others’. There were boots everywhere, from the farmers I met in Transylvania to the tiny feet of Romanian President Ion Iliescu.

I had bought my boots in Texas, where I had them specially fitted. My favorite part was the moment when I gave a tug on the bootstraps and my foot slid smoothly and snugly into place. 1) Toe in; 2) grab loops and pull; 3) a second of stasis as my foot hesitates then slides smoothly all the way in, where it is held firm by the leather.

Snug and secure, they gave me –or my feet at least – sensual comfort plus a sense of invulnerability.

I was glad to have them the night I arrived in Bucharest. I’d gotten to the hotel late and I wanted to get a sense of the city before I went to sleep so I decided to take a walk.

It was past midnight when I stepped out of my hotel in Central Bucharest, About half of the streetlights were working, so there were deep shadows on my journey through the dingy downtown. As I walked I heard the occasional crash of garbage cans on a side street and once or twice, a bark or a growl.

As I approached a particularly dark block, all of its streetlights extinguished, I noticed some movement in the shadows and then suddenly a half-dozen or more stray dogs running my way, snarling and barking as they got closer. I looked around and didn’t see another person in either direction.

I turned and ran, my boots landing on cobblestone sidewalks slick and puddled from an earlier rain. The boots, with their leather soles, slipped and slid as I ran and no longer felt quite so protective. The dogs pursued, picking up their pace. In my mind’s eye I saw myself losing balance, then sprawled out on the pavement as the feral canines lunged for my throat.

Then I saw the stoop of a century-old block of flats and a man just approaching the door. I bolted up the stairs to him. He looked alarmed, then his gaze focused behind me on the pack of dogs. ``Help,’’ I pleaded, gasping for air. He opened the door and pulled me inside.

I stood in a dim hallway struggling to catch my breath. I was a smoker in those days and I felt like I was suffocating after my short, terror-filled run. ``Wait,’’ the man said before opening the door to an apartment. He returned a minute later with a glass of water. The dogs by this point were gathered at the door, yelping and growling. ``Wait,’’ the man said again, pointing toward the dogs.

``The dogs, they own the streets,’’ the man said in English. He pulled up his pants leg to show me a nasty scar, apparently from a bite.

Eventually, a car passed and the dogs took off in pursuit. I took another drink of water and a deep breath and opened the door and stepped outside. The pack had gone so I moved quickly down the stairs and back up the street to my hotel.

I had lined up an interview with the Romanian president and was instructed to come to his residence, the 17th-century Cotroceni Palace. I wore my best blue suit, with a wide tie in a hideous green and blue pattern, and my cowboy boots.

At the palace, I was met by ceremonial guards in blue tunics with a double row of buttons, red epaulets with gold braids and white pants with a gold stripe. And boots -- tall, black and shiny.

I called the guards ceremonial but they were actually quite aggressive. They asked for my passport and then refused to return it. (``When you are finished here,’’ the man said in a slightly malevolent tone.)

I was already feeling a bit paranoid. All those boots and gold braids and the massive palace with stone staircases and red carpets, not to mention the general air of hostility of the guards. I was led down an arched hallway and through a door into what looked like a throne room. The walls were white and gold and at one end of the room were a few steps up to a throne-like chair.

It was all very intimidating.

Then the president arrived. As he climbed the dais, I realized he was quite short (Wikipedia says 5-foot-6, but I would have said 5’4’’ at most). He had thinning gray hair and wore a dark gray double-breasted suit with a red tie (also wide -- it was the fashion at the time).

And boots.

White boots. His pants weren’t tucked into the boots but they were short enough to qualify as what we used to call ``high waters’’ when I was a kid, so his Go-Go boots, about mid-calf high, were in full view.

Then, adding even more emphasis to the odd presidential footwear, once he’d climbed up on the throne, his feet dangled about three inches above the floor.

I stood and introduced myself and asked if I could set up my tape recorder. He agreed and we engaged in a bit of small talk - ``First time in Bucharest?’’ he asked. ``No, my second,’’ I replied.

My first visit had been a year or so earlier. I had interviewed the privatization minister, who was busily selling off the state-owned phone company and stakes in utilities and beer makers and even weapons makers.

I admired his watch, a Rolex.

``A gift from our business partners,’’ he said.

``Of course. That’s what I assumed,’’ I replied.

So this time I had a bit of a sense of the environment, though now, as I prepared to interview the president, a new government was about to take charge. So maybe things would be different. I was here to find out.

Though honestly, I couldn’t take my eyes off Mr. President’s white Go-Go Boots.

I set up my tape recorder and as I was introducing myself and explaining my news organization, several large men came through the door, wheeling a TV camera. It was the biggest camera I had ever seen up close. It was on wheels and had a round metal base that the operator stood on. It reminded me of the cameras I had seen on the Allen Brady Show, the show within the Dick Van Dyke show. Very much ‘60s-era hardware, the kind where the operator walked around the metal ring at the base of the massive machine to control the camera angle.

Finally, the camera operators signaled they were ready, so I turned on my tape recorder and started the interview.

So, I asked the president, if you win the election, what is your model for the economy you want to build here now?

``Well,’’ he said, ``The greatest economist in history is Comrade Stalin.’’

I guess I shouldn’t have been as stunned by this as I was. I couldn’t manage to say a word for at least half a minute. But Iliescu in this one way at least was being true to himself. He’d been the right-hand man of Romania’s communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu until just before he and his wife were tried on charges that included subversion of state power and genocide by starvation – the crime that Stalin committed on an unprecedented scale, yet never faced charge. After a two-hour trial and the inevitable guilty verdict, the Ceausescus were hastily executed by firing squad.

Iliescu’s comment at the time was that the executions were ``quite shameful, but necessary.’’

And yet, like Stalin in Russia, even today there are Romanians who remember the dictators fondly, leaving flowers on their graves in the Ghencea Military Cemetery in Bucharest even these three decades later.

``Totalitarian regimes are very efficient for the accumulation of capital, for the development of national industry, for organization, even for some social achievements,'' he said. ``From the political and social point of view, limitation of the free expression of values proves to be very

inefficient for social relations, of course. But even from the economic point of view ... technological progress needs more flexibility.''

Wow. And what about the millions sent to the Gulag or murdered or worked or starved or tortured to death?

``Regrettable. Of course.’’

And then he moved on. His plans to privatize, to join NATO and the European Union.

As I packed up and retrieved my passport, my head was still spinning. I took a taxi to my hotel and started writing. The president’s adoration of Stalin made for an easy lead.

The next morning, I descended to the lobby restaurant in my hotel for breakfast and got a shock. There was a stack of Romanian newspaper and my byline was on the front page of three of them. My Romanian is pretty limited but I could tell there was a little introduction to the story saying that Rob Urban of the New York Times had interviewed the president. This was strange as I didn’t work for the New York Times. Never have.

The story itself, as far as I could tell, seemed to be unchanged from what I had filed.

Oh shit, I thought. I’m probably not too popular here. The journalist who revealed their president is a Stalinist.

I was meeting a Romanian friend that day who had promised to take me to the mountains of Transylvania. I wanted to talk to people in the countryside and small towns about the election.

Paul was waiting in the lobby when I went down. ``Well, well, well,’’ he said. ``New York Times.’’

No, I said. I don’t know where that came from (I figured out later that my story had been carried on the New York Times wire, so that must have been where the confusion started).

We got in Paul’s car and headed out of town. The roads were narrow, with lots of blind curves and as we came around some of them, Bogdan was forced to slam on the brakes as we came up behind a horse-drawn wagon.

As we followed the road up and up into the Carpathians, it started to snow.